Subscribe to eyeMatters periodic news

"*" indicates required fields

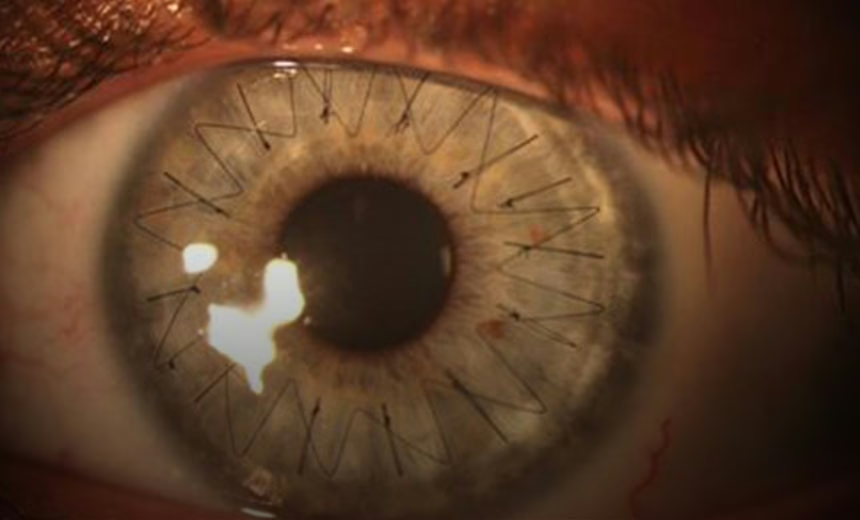

Demystifying corneal transplantations

The cornea is a curved, clear layer that lines the front of the eye – it can be thought of as the eye’s ‘windscreen’. A number of conditions can affect the cornea (e.g. keratoconus, Fuchs’ dystrophy, keratitis, ocular herpes) and impair vision. If other available treatment options do not work or have stopped working, a corneal transplant may be recommended to restore sight. Although corneal transplantation is the most frequently performed transplant procedure in the world, there are still a lot of misconceptions about it that I’d like to address.

- Your eye colour will not change after a corneal transplant. Eye colour is determined by the part of the eye called the iris, which sits under the cornea. The cornea itself is clear, so replacing it won’t change the colour of your eye.

- Unlike organ transplants, the donor and recipient don’t need to ‘match’ on factors such as blood type or HLA type (immune system markers). Donor age, eye colour and vision are also irrelevant. The main criteria when assessing donor corneal tissue is that it is healthy and intact. People with infections or diseases such as HIV and hepatitis are not able to donate their corneas.

- Even though a blood match isn’t needed, a corneal transplant can still be rejected by the body. Rejection occurs when the body recognises the donor tissue is foreign, which triggers an immune response. This can happen in about 20% of cases and can occur soon after surgery or decades later. An illness or injury may trigger rejection of the transplanted tissue, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it needs to be removed. Signs for tissue rejection include redness in the eye, light sensitivity, vision loss and pain. If started early enough, anti-rejection medication may be able to bring this under control. If medication is unsuccessful, a new transplant may be required.

- Corneal transplantation can be used to treat a number of conditions, including keratoconus, Fuchs’ dystrophy or corneal oedema. Sometimes, a transplant is needed because of significant corneal scarring (e.g. due to ulcers, injury or infection).

- Corneal transplantation is not new – the first successful transplant was performed in 1905. Over the years, the technique has been further developed and refined. Through my research, I have developed new techniques for corneal transplantation, including pioneering the use of a single donor cornea to treat three different patients.

- Two main methods are used to perform corneal transplantations. The difference between the two is the amount of corneal tissue that is replaced. When all five layers of the cornea are removed and replaced, this is known as a full-thickness transplant. On the other hand, a partial-thickness transplant involves replacing only the affected corneal layers and is called customised corneal transplant surgery.

- Corneal transplants may not last forever. The length of time that the transplant lasts will depend on the initial reason for the transplant and type of corneal transplant performed i.e. full-thickness or partial-thickness. Fortunately, patients can receive multiple corneal transplants.

- Contact lenses, glasses or laser eye surgery may be required to improve vision following a corneal transplant. This is necessary if the transplanted cornea does not achieve the precise rounded shape required for clear vision.

Advances in the field of corneal medicine mean that alternative treatments may soon be possible, bypassing the need for corneal transplantation altogether. For example, we might soon be able to fix some patients using the iFix Pen, a novel device that my colleague Professor Gerard Sutton is collaborating on with a number of others. The iFix Pen delivers a bio-ink formulation to injured corneas to promote healing and prevent infection. Corneal tissue used in transplantations is generously donated by people who have opted to be donors.

All medical and surgical procedures have potential complications – check with your ophthalmologist before proceeding.

The information on this page is general in nature. All medical and surgical procedures have potential benefits and risks. Consult your ophthalmologist for specific medical advice.

Date last reviewed: 2023-11-10 | Date for next review: 2025-11-10